Qualitative research is typically concerned with exploring perceptions and views, unpicking behaviour and understanding experiences. It is often used to answer research questions beginning with ‘how’, ‘what’ or ‘why’, such as ‘how do prospective students make decisions about which universities to apply to’, ‘what is the experience of getting a higher education degree during the COVID-19 pandemic’ or ‘why are certain groups of students less likely to apply to certain courses’. This guide explains how to carry out an effective qualitative research study, from design through to analysis.

Qualitative methodologies

There are many forms of qualitative research. This guide will focus on the three most common methodologies and how to best use them.

In-depth interviews

In-depth interviews provide you with an opportunity to collect detailed and rich information from each participant. They allow you to understand their experience and to explore their attitudes, beliefs and motivations in great depth. One-to-one interviews are also more suitable for discussions of sensitive topics, as they allow the interviewer to build trust and rapport with the participant over the course of the conversation.

Focus groups

Focus groups can be an effective way of speaking to a larger number of individuals at one time and are often used when the conversation topic would benefit from a group dynamic. For example, a group discussion might help you get beyond ‘top of mind’ responses and get participants to question their own attitudes or views when confronted with someone else’s. Focus groups are also commonly used to ‘test’ new concepts e.g. a re-branding exercise.

Ethnographic observations

Ethnography means observing research participants in ‘real life’ contexts and to better understand social interactions and behaviour. It is often used to add more depth or nuance to information collected through interviews with participants. In addition to direct observations, ethnographies sometimes include things like diaries, video recordings and photographs.

Designing a good topic guide

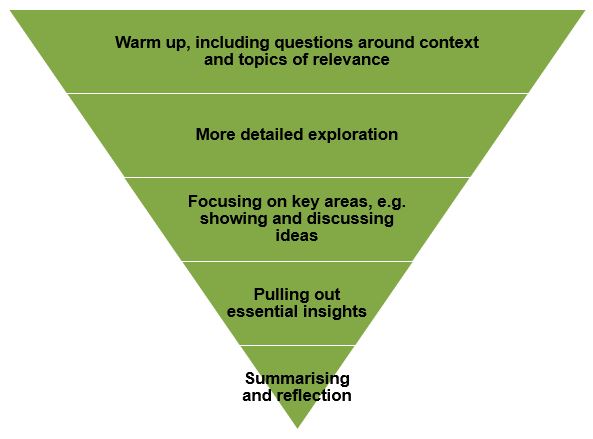

Effective depth interviews and focus groups require a user-friendly topic guide. It should outline the key research questions and steer the discussion but should not limit it or make the conversation feel rigid or forced. Some key considerations when structuring a topic guide include:

- Allow enough time for a proper warm-up: Investing in a proper warm up puts participants at ease and increases your chances of getting high quality insights from the discussion later on.

- Be honest about the time you have available and precise about timings – make priorities, what it essential and what is nice to know: Start by writing a list of all the question you want to ask, group them into themes and consider the most natural way to sequence the themes. Consider how much time you have available and make priorities. Add timings to each of your sections and be honest about long it is likely to take. You don’t want to risk running out of time before being able to ask some of your essential questions.

- Keep it simple: A long and detailed guide is not practical to use in an interview. It is inflexible, draws focus away from the participant, and interferes with building a relationship with them. Keep it simple, easy to read and navigate and use simple prompts or probes.

- Take an exploratory approach and narrow the focus as you go: It is common to start a topic guide with a broad focus and narrow the question areas as you go. You may also want to set aside some time at the end for a summary and reflection of the conversation.

- Use activities to keep participants engaged: Practical activities or exercises help break up the discussion and avoid ‘interview fatigue’ during longer interviews or focus groups.

Top tip: Test your topic guide on a colleague to check is fit for purpose or needs amending before you start interviewing ‘real’ participants. As a rough guide, limit the length of your discussion to no more than 45 minutes for a one-to-one interview and an hour and 45 minutes for a group discussion.

Conducting qualitative fieldwork

A good interviewer or moderator needs to be able to put the participant at ease, have good listening skills, ask good questions and manage the interview to ensure you answer the key research questions but still reflect the thoughts and opinions of the participant.

Putting the respondent at ease

Remember that most people have not taken part in market research before and might be unsure or even nervous. Allow enough time to put the participant at ease and to ‘warm up’. Be aware of your own body language, your tone of voice and the energy you are bringing– smile, encourage and assure.

Active listening

Listening is of course a key skill in a good moderator. A strategy often used in qualitative research is active listening, which broadly means trying to understand what your participant means, rather than just what they say. The result is really understanding what the other person means, and the other person feels understood. As part of this technique, the listener verbally feeds back what they hear and / or what they notice about the speaker. The speaker can then either agree with the listener’s interpretation or correct them. In addition to reflecting back what the participant is saying you should notice and reflect back their tone of voice, body language and emotion. For example, you might say:

- “So, I am hearing that you felt the course facilitator did not tailor the session to your needs, is that right?”

- “This sounds like something which was quite upsetting for you?”

- You can also reflect back any contradictions or things the speaker is not talking about:

- “I get the impression this isn’t something you want to talk about. Is that right?”

- “I noticed that earlier you said xxx but now I’m getting the impression you might be saying something quite different?”

Active listening allows you to get beyond ‘top of mind’ responses and dig deeper into a participant’s views, attitudes or behaviour, while ensuring the participant feels heard and understood.

Asking the questions

A key element of effective qualitative interviewing is asking open rather than closed questions. While closed questions encourage a brief answer and influence the answer the speaker gives, open question allow and encourage a free response. Below are some examples of closed and open questions.

Closed questions

Is that when you decided to apply?

Did that make you feel frustrated?

Did you decide to become an engineer because you went to the careers fair?

Open questions

What happened next?

How did you feel about that?

Tell me why you decided to do that.

Why do you say that?

Can you tell be more about that?

Remember, the best questions are those that elicit long answers and require little follow up questioning, beyond simple prompts or encouragements (e.g. ‘why is that?’).

Top tip: If a participant can answer a question by simply saying ‘yes’ or ‘no’, don’t ask it!

Practical tips for during the interview

These are some common challenges in qualitative interviewing and tips for how to respond:

- Participant talks too much or goes off topic: Set expectations at the start, explain what you will cover in the interview and that you might need to steer the conversation to ensure you cover the key questions. If the participant digresses, give them a moment to do so and then gently steer them back.

- Participant talks too little: Acknowledge this and explore why. For example: “You’re not saying very much about this, can I ask you what you’re feeling at the moment?”

- The participant gets upset or angry: Acknowledge it as it happens and give them time and space to process what they are feeling. Offer them to take a quick break before continuing the interview.

- The interview involves sensitive topics: Prepare – make sure you know the topic guide well and feel confident in your phrasing. Give participants the option not to answer questions.

- The participant expresses views you disagree with: Don’t offer your own views – it will change the dynamic of the interview in an unproductive way. Paraphrase back what they have said and if you are asked for your opinion explain that your role is to listen and to understand, not to offer your own take.

Practical considerations

Ensuring accessibility

Ask each participant whether there is anything they need in order to take part in the research at the point of recruitment. This could include things like translators or making sure written materials are accessible, but could also include having a friend, family member or other trusted person present during the interview. If doing the research online, make sure they have the necessary technology and software.

Ethics and data protection

Along with your topic guide, it is useful to prepare a checklist to go through before you start the interview. This should include:

- Has the participant read, understood and signed the relevant consent forms and information leaflets?

- Have you made the participant aware of how you will use, store and delete the data you collect and their rights under GDPR?

- Do you have explicit permission to record the interview?

- Does the participant have any questions for you about the materials you have shared or about the research more broadly?

Analysing your discussion

There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to qualitative analysis. Different methods and tools work for different people. Below we discuss some common tools and approaches.

- Analysis starts within the interview itself: By making sure you are prepared for your interview and know the topic guide and key research questions well, you create ‘mental space’ to carry out informal analysis during the conversation. During the discussion, ask yourself “what does this mean for my research questions? What are the implications?” This allows you to probe topics relevant to your objectives during the interview and build on what you already know.

- Write up a short summary of the interview as soon as possible after completing it: Writing up the key findings or themes, as well as anything which surprised you, shortly after the interview will save you valuable time when you move into the analysis and reporting phase. If the interview revealed valuable quotes or case studies you should highlight this in your notes.

- Data management is a necessary pre-cursor to analysis: Before you can draw out the key themes in your data, you need to organise it. This might involve things like colour coding, categorising, mapping or counting and will help you get a better overview of the information you’ve collected.

- Identify ‘keyness’, develop overarching themes and a narratives: ‘Keyness’ is not merely based on the frequency of recurrence (i.e. what most people said) but also relevance (e.g. something said once could be the final ‘piece in the puzzle’). This should always relate back to the objectives.