This article was originally published on Wonkhe on 27th September 2021 titled ‘Moving the Graduate Story Beyond Employment‘

The idea of graduates living an enriched and fulfilling life is one that has guided the higher education sector for a long time. Students go to university, not just to “get a degree to get a job” but to become more rounded individuals equipped with the skills and nous to deal with whatever life has to offer them.

However, until now, the reporting of successful higher education outcomes has focused mainly on employment; how many graduates are in paid work, whether they’re in “professional” occupations, and what salary they earn. This only showcases part of the impact higher education can have, and doesn’t consider the higher education experience in a truly holistic way or the broader outcomes graduates achieve.

How does it work?

The Graduate Index is a survey that measures graduates’ successes across seven social and personal measures:

Within each area, graduates are asked a series of specific questions and based on the answers they provide, are assigned a Graduate Index score out of 100. The seven index areas are given equal weighting when calculating the overall Graduate Index.

Graduates’ scores can be grouped to demonstrate the relative performance of different subject areas, university groups, study modes and levels or key graduate demographics. By asking graduates how they think they are getting on in life beyond employment, we feel that the Graduate Index truly captures a more rounded picture of the longer-term impact of the higher education experience.

What insight does the Graduate Index provide?

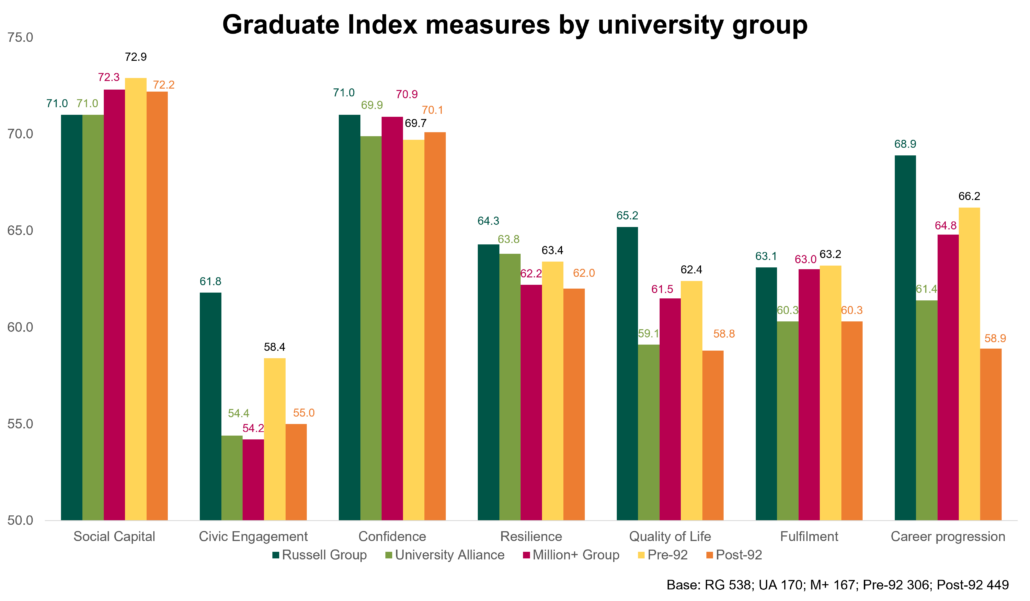

The research has thrown up some really interesting findings with overall Graduate Index scores higher among graduates of Russell Group universities, males graduates and postgraduates. Looking at the individual index measures, however, reveals a more nuanced story. So, while graduates from Russell Group universities, perhaps predictably, outperform other university groups on career progression and quality of life, they perform relatively poorly on social capital and are on a par with others in terms of fulfilment and confidence.

One particular area of interest is that the variance in Graduate Index scores is greater by subject than by university group. This suggests that the subject a graduate studied appears to have greater bearing on the Graduate Index score than the type of university they attended. A timely finding in the context of the government’s looming Spending Review and what that might mean for funding to universities and of specific courses.

If funding ends up being contingent on the perceived value of a course, then how “value” is defined is more important than ever. If a subject reports higher levels of social capital but lower levels of resilience (as is the case with graduates of Education subjects who took part in the research) does that mean that subject is more valuable than another which produces more consistent, but slightly lower scores across all 7 areas of the index? Could you argue the subject that doesn’t score quite as highly but does score more consistently produces more rounded graduates?

There are also other considerations to take into account like graduates’ motivations for studying a particular subject and what they wanted to get out of the experience – confidence might be more important to some graduates and less important to others. Using the Graduate Index alongside these considerations provides a new context.

Universities running their own Graduate Index survey will be at the forefront of these conversations. They will have a detailed understanding of the wider impact their provision is having – how different courses produce different social and personal outcomes for their graduates. This can then be overlaid with analysis by key demographics and socio-economic characteristics.

For example, to what extent is there a gender imbalance in terms of the confidence and resilience of their graduates from different programmes? Or how are their students from disadvantaged backgrounds faring in terms of their wider outcomes? If results from this research were mirrored for their own Creative Arts graduates, universities will know that they struggle on five of the seven measures but perform relatively well in terms of confidence and social capital. However, when you look at scores by gender, we see that female graduates of this subject area achieve a lower overall score than male graduates and apart from social capital, also score lower across each component area. In particular, female Creative Arts graduates score lower on the quality of life measure than their male counterparts and this seems to be driven in the main by lower mental wellbeing scores and lower levels of disposable income.

Used alongside other existing datasets that focus on more traditional outcomes as well as other datasets universities might hold themselves on applications or careers registration, this invaluable insight can be used to target certain courses for particular interventions designed to improve specific outcomes, or by careers and employability teams to support certain student groups.