How do you evaluate a pilot in a field as complex as the judicial system?

It can be hard given practical limitations such as timings, location and budget, and the sensitive and complex nature of the work. Good evaluation can equally be affected by the need to delve into services without disrupting them. And that was before the pandemic…

We worked in partnership with Frontier Economics to tackle this question and more, in the evaluation of the Flexible Operating Hours (FOH) pilots, now published.

HM Courts and Tribunal Service (HMCTS) set up FOH to look at maximising the use of time in specific court and tribunal hearing rooms to support a more flexible, efficient and effective justice system. We set out to understand:

- Whether longer court operating hours mean that a greater proportion of court time is devoted to productive uses, with less time where the court is not in use

- Whether operating courtrooms at different times of the day offers more open and accessible justice to citizens

- Whether and how FOH impacts professional and public court users, and the agencies working in the justice system.

FOH pilots

The FOH pilots involved afternoon and late sittings in courtrooms in Manchester and Brentford between 2nd September 2019 and 13th March 2020. In Manchester, the pilot was implemented by shifting the timing of the usual court sessions (i.e. those sessions taking place during usual hours), while in Brentford, pilot sessions were run in addition to business as usual sessions.

In Manchester, cases heard during FOH sessions were small claims, non-small claims, civil and financial disputes, family cases (not including children’s work); while in Brentford, small claims and non-small claims civil cases were heard.

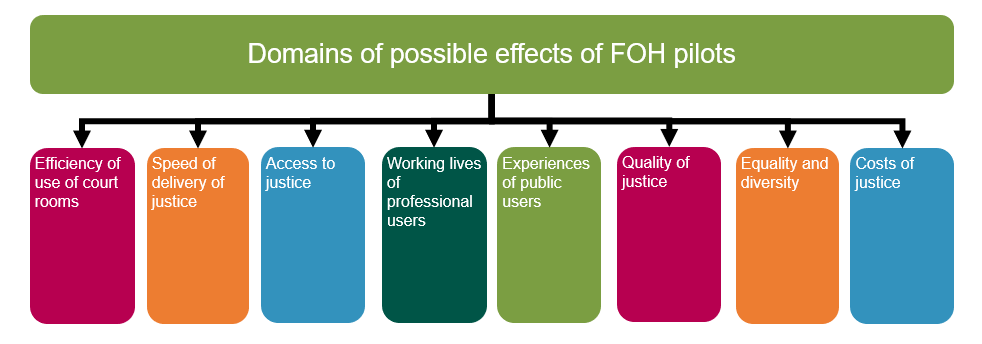

The evaluation aimed to assess the impacts of the FOH pilots across eight domains of interest:

To do so, ideally the pilots could randomly assign users to FOH sessions (‘treatment’ group) and usual sessions (‘control’ group) to rule out factors other than FOH causing any changes observed. And ideally, we would have comprehensive sources of evidence relevant to all the above domains of interest to explore the effects of the pilots across different audiences. But the real world of course throws up challenges, and the perfect solution is rarely feasible in practice. As evaluators, we’ve learned to welcome these challenges as opportunities to be creative!

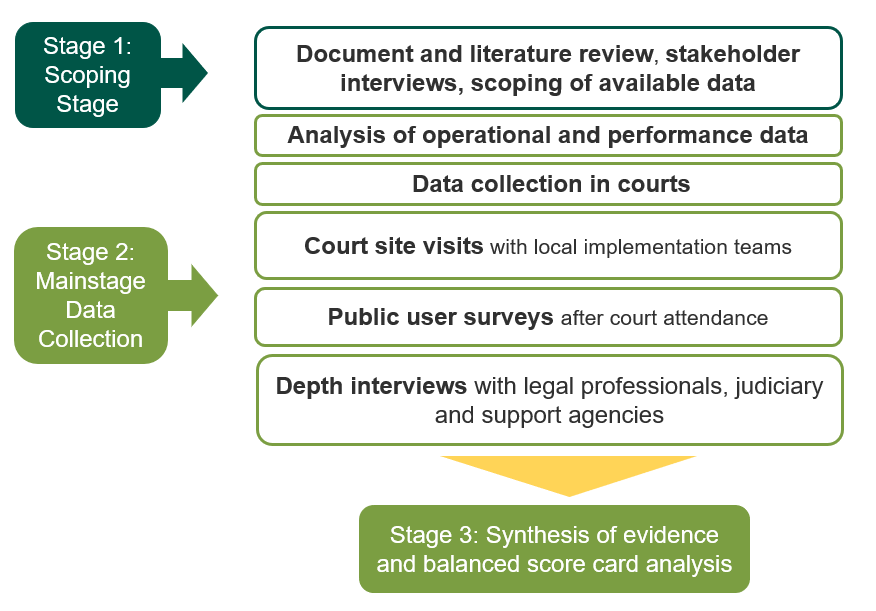

Instead, we conducted analysis of operational, performance and cost data, comparing evidence collected during the pilots with evidence from before it launched. You may be thinking, “What does that even mean?!” Our partners, Frontier Economics, analysed:

- case level data from HMCTS’ centralised databases;

- data on claims for the pilot participation fee;

- data on the Housing Possession Court Duty Scheme claims; and

- data on the number of profile and sitting days by court.

We also interviewed court staff, legal professionals, judiciary and support agencies across the pilot’s operations, encouraging them to compare their views and experiences during the pilots with business as usual. It was fascinating seeing a picture gradually emerge from our interviews and visits to courts.

We were aware public users typically go to court once, so we could not compare experiences of going to court in FOH with their experiences of going during business as usual hours. To solve this, we surveyed two sample of public users – those that attended an FOH session and those that attended court before the pilots began – and compared their views and experiences at a ‘big picture’ level. Overall, the evaluation captured the views of 78 court staff, judiciary and legal professionals, 124 public users involved in the pilot, 453 public users of the courts before the pilot and 24 public users that opted-out of the pilot.

Each of these data sources were used to create performance indicators to assess the impact of the FOH pilots in each of the relevant domains of impact.

The figure here summarises the evaluation approach.

Findings

Overall, if additional judicial and staff resource is put into flexible hearing times, then this will enable more cases to be heard within existing court rooms; and this is likely to be a more convenient option for some members of the public and individual legal professionals. However, there are indications that the FOH sessions created additional childcare issues for some court staff, professionals and members of the public; and legal professionals were of the opinion that this scenario risks placing disproportionate burden among women and junior barristers within the legal profession. This suggests that, if pursued more widely in future, participation in FOH might need to continue to be a matter of choice for some members of the public and legal professionals.

The FOH pilots appear to have had a broadly neutral effect on efficiency of court room use, for example, the FOH sessions were at least as efficient as the pre-pilot sessions. Given that FOH sessions do not appear any more or less efficient, on balance, than pre-pilot sessions, FOH could feasibly lead to increased productive court time, if FOH sessions are undertaken in addition to business as usual.

The FOH pilots appeared to have had an indicatively positive effect on accessibility of justice to citizens, with some evidence of reductions in time taken off work and improvements to perceived convenience of hearing times and travel to and from court. That said, some legal professionals, legal organisations and court staff raised concerns about FOH sessions being difficult to access for some public users, namely those with childcare responsibilities, those who are financially vulnerable or who do not live near the court.

The FOH pilots had some positive effects on public court users, namely on public user satisfaction with case outcome, their perceptions of quality of justice, and reduced average waiting times. Legal professionals and some members of the judiciary were, however, concerned that longer working hours had affected legal professionals’ energy and concentration levels. The reported effects of the FOH pilots’ on the working lives of legal professionals tended towards the negative.

Back to our initial question: How do you evaluate in a field as complex as the judicial system?

The short answer: methodically map what information is available or could be available to capture evidence on your intervention, expect the unexpected, and collaborate with all involved in the evaluation to work out what is practical, proportionate and adds value. And anticipate the time, attention to detail and skill required to combine multiple sources of information on the court cases of interest and details of the legal professionals and public users to produce a useable sample frame.

The long answer: read our carefully crafted technical report.